DREWRY’S Container Forecaster report is predicting that annual profits for the industry could exceed US$100 billion. Maersk, the world’s biggest container shipping line, is forecast to make about US$14.5 billion this year.

Compared to land-based companies, shipping lines are often taxed based on their tonnage rather than income or profit. Tonnage tax creates a predictable, consistent and usually low tax expense. In a year where profits are low, or losses are high, the corporate tax bill remains the same as in the good years when profits are high. For instance, Maersk’s effective tax rate was less the 5% during the most recent six-month period according to Bloomberg. This probably means that of the US$100 billion, very little will end up in government’s coffers.

There is currently a push for the introduction of a global minimum effective tax rate (15% is being mooted) that would apply to groups with annual gross revenues in excess of US$750 million and seeks to have companies pay their taxes in jurisdiction where their customers are based. This would include shipping lines but so far, they have managed to avoid becoming subject to this tax regime.

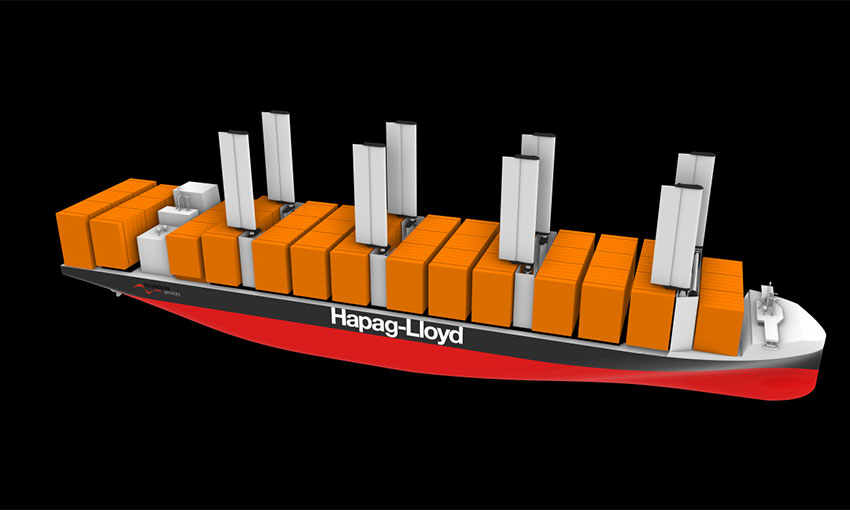

The latest profits, which come after many years of negative or very little returns, should set the shipping lines up for years to come and has spurred on investment in an extensive new shipbuilding program. The orderbook currently stands at 5.3 million TEU, with 16,000-TEU ships being the most popular, according to the Baltic and International Marine Council (BIMCO) with the majority scheduled for delivery in 2023.

Big shortages

There is currently a shortage of container vessels as well as containers. The shortage is due to a number of factors, the main one being the COVID pandemic, which caused imported goods to surge, compounded by port closures and queues of container ships waiting to unload at some of the major ports in the world.

There’s even talk about converting open-hatch vessels so they can carry containers. For older DCN readers, this brings back memories of the infamous ABC Container Line round the world service, which used to call at several Australian ports, that went into receivership in 1996 leaving many creditors, including stevedoring companies, out of pocket. The line used a type of vessel that could carry containers as well as breakbulk. Container stowage in the forward hold was a nightmare, as a heavy forklift had to be used below in order to stow the containers athwartships five high in the wings causing all sorts of difficulties and safety issues.

Will the boom last?

The shipping industry is used to a boom or bust scenario and is sometimes its own worst enemy by flooding the market with additional capacity that causes a price war to fill the ships. In view of the new shipbuilding program being undertaken at the moment, the question is will that happen again? Industry experts expect not, as consolidation in the industry (80% of global container shipping capacity is controlled by 10 operators) and retiring of older ships in the fleet will keep the market balanced, certainly for the next few years. For shippers this will most likely mean a continuation of high prices for container bookings.

Time will tell if we have another black swan event such as the COVID pandemic, or will it be more plain sailing and calmer waters for the shipping and logistics industries in the years ahead.

Peter van Duyn

Maritime logistics expert, Centre for Supply Chain and Logistics, Deakin University