IN NOVEMBER 2022 insurers TT Club and UK P&I Club and scientific consultant Brookes Bell published a whitepaper suggesting the risk of transporting lithium-ion batteries poses a greater threat to the maritime supply chain than the industry realises.

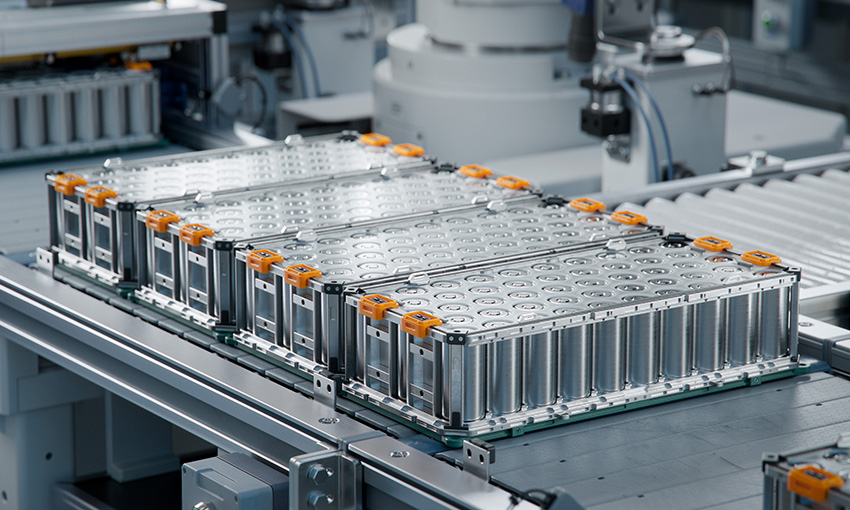

Lithium-ion batteries offer portable power, energy efficiency and a lighter alternative to traditional battery types. The research department at Statista projects that, between 2022 and 2030, global demand for lithium-ion batteries will increase almost sevenfold.

Lithium-ion batteries travel along the maritime supply chain in handheld devices, electric vehicles and sometimes within the ship itself. Most of the time the vessels and cargo reach their destinations safely, but on rare occasions of battery failure, the consequences can be catastrophic.

RISKS AND PREVENTION

Ian Gabites, a lecturer in shipboard fire prevention, safety and firefighting at the Australian Maritime College, released a timely paper in November 2023: Lithium-ion batteries – Everything currently known and what needs to be considered to inform, to prepare and to manage risk.

According to Mr Gabites, the rapid development and subsequent abundance of lithium-ion batteries is now impacting safety. Lithium-ion batteries that are misused, abused, physically damaged, overheated or over charged are likely to go into thermal runaway – a failure of a battery cell that causes an intense fire and potentially an explosion.

Mr Gabites in his paper looks at the challenges and strategies for fighting ship fires caused by lithium-ion batteries, as well as preventative measures to avoid thermal runaway in the first place.

“I think eventually we need to train people better to recognise what could be a problem well before it becomes a problem,” he told DCN.

“A smashed battery is the battery that’s going to catch fire, if it’s going to catch fire. On the upside, it happens very rarely. The downside is, when it happens, it’s bad.”

NOT JUST CARGO

In early 2022, the ro-ro vessel Felicity Ace caught fire south-west of the Azores archipelago, burned for two weeks and eventually sank. The ship was transporting about 4000 cars, including electric vehicles. Mr Gabites’ paper notes it is widely presumed that one of the vehicles caught fire, causing a chain reaction of ignitions in neighbouring vehicles.

Mr Gabites outlined three sides to the risk of transporting lithium-ion batteries: containerised goods, electric or hybrid-electric vehicles and onboard tools and devices. He said almost every lithium-ion battery attached to a tool or electronic device in Australia had to be imported, often as containerised cargo.

“We need to take some precautions with that; we don’t know the quality of the battery and we can’t see in the container very often. So how do we look after that container?

“A battery that’s damaged or manufactured poorly is going to be alongside a lot of other equipment with more batteries. If one catches fire, the lot catches fire, and in a container situation that leads potentially to an explosion.”

But the third side of the risk isn’t cargo at all. Early last month the US National Transportation Safety Board published the findings of an investigation into a fire that destroyed the bridge of an oil tanker. S-Trust was docked in Baton Rouge, Louisiana in November 2022 when a handheld UHF radio caught fire. The NTSB found a cell in the radio’s lithium-ion battery had exploded. No injuries were reported, but the fire resulted in about US$3 million in damage to the vessel.

“We’re also moving into the autonomy and battery powered vessel era,” Mr Gabites said.

He pointed to an incident on the Norwegian ro-pax ferry MF Ytterøyningen in 2019. The vessel had recently been converted to a battery-hybrid ferry and was running on diesel engines when a fire broke out in the battery room.

If the industry can take anything away from incidents such as the Ytterøyningen fire and, presumably, the sinking of Felicity Ace, it’s that lithium-ion battery fires do occur on ships, Mr Gabites wrote. They can cause expensive damage quickly and without warning which, according to Mr Gabites, puts crews at risk of acute and chronic injury or death.

A NEXT-LEVEL THREAT

Mr Gabites, a volunteer firefighter of 29 years, said there are similarities between ships’ crews and volunteer fire brigades. Seafarers and volunteer firefighters have their day jobs, they may train once or twice a month, and they respond when the alarm sounds. He said all crews are fire-trained, but training is often not as frequent as it could be.

“Their day job is to get stuff on the vessel, off the vessel and move the vessel from here to there and back again. They probably don’t see fire as a very high priority in the big scheme of things … it’s just a little part of a large role they play in the transport of goods around the world.”

A lithium-ion battery fire is a uniquely challenging fire to deal with, however; a self-oxygenating fire is extremely hard to extinguish. Responders cannot approach the fire because it creates jet-like flames and emits toxic gas at a high rate. There might be thousands of cells surrounding the one that caught fire, and they are likely to ignite as well. Secondary burning can occur hours, days, weeks or even months down the track. The IMDG code advises that fire parties use copious quantities of water from as far away as possible. This may not be to put the fire out, but to prevent the spread of fire to neighbouring cargo.

“If a battery pack catches fire – it doesn’t matter if it’s a portable device or an EV or anything in between – keep your distance and pour water on everything around it. Don’t worry about the fire itself, because there’s nothing you can do about it.”

Even smoke from battery fires can be deadly; the toxic gases can be breathed in or absorbed through the skin. Vapours can find their way through gaps in protective fire suits.

“The standard fire suit is designed to protect you from radiant heat; it’s not necessarily designed to protect you from airborne contaminants,” Mr Gabites said.

“There’s a whole new subject matter of contamination of firefighters and cancer and other terrible things.”

And if a device on board – such as a UHF radio – starts smoking, Mr Gabites said the best thing to do is pick it up with a metal dustpan (for example), hold your breath, and throw it overboard.

“Get rid of it, and then have a damn good wash.”

TRAINING RESPONSIBILITIES

Mr Gabites said there needs to be a topdown approach to regulation, education and training for lithium-ion battery fires. He said International Maritime Organization model courses for STCW Fire Prevention and Fire Fighting and Advanced Fire Fighting are due for an overhaul – they were last reviewed sometime around the year 2000. A review of Advanced Fire Fighting has been ongoing for several years, but Mr Gabites said the review may need updating again by the time it is released.

“There’s some old stuff in those model courses that could be ditched in place of more modern, contemporary problems that are arising,” he said.

“And from there, once the IMO takes it on, organisations like the Australian Maritime Safety Authority can start to feed it through.”

One of the problems with infrequent or overdue fire training is that if a crewmember misses monthly training due to sickness or time off, the months in between sessions could impact their efficiency or response in an emergency. For example, they may forget to put their breathing apparatus on.

Mr Gabites also highlighted the need for wider training in identifying damaged battery packs, to avoid fire in the first place. He believes the whole supply chain needs to be trained to avoid damaging cargo such as electric vehicles when loading and unloading vessels. Everyone should know what to do when a fire starts.

“I think we need an industry-wide look at the subject so we can come up with some common ground that we can then refine.

“And that way, there’s support across the industry from the top down rather than from the bottom up, which rarely happens successfully.”

Another possible consideration is ensuring water can reach burning cargo on increasingly large ships.

“As container ships get bigger and bigger … getting to those places is going to be more and more difficult. Twenty years ago, a containership was rather a small thing with plenty of gaps. These days, it’s not, because space is money. That could be an interesting conundrum.”

This article appeared in the December 2023/January 2024 edition of DCN Magazine