THE time is ripe for the world’s major energy exporters to accelerate the energy transition, and mastering the hydrogen trade could make a difference, according to analysts at research and advisory firm Wood Mackenzie.

The global energy market was worth US$2 trillion in 2020, contributing to more than nine billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions. In the same year, the top five energy exporters – Saudi Arabia, Russia, Australia, the United States of America, and Indonesia – produced more than half of all energy traded.

Wood Mackenzie research director Prakash Sharma said, “The global energy trade is set to see its largest disruption since the 1970s and the rise of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

“In addition to investing in renewables to slash emissions and enhance energy security, countries and industries are now looking to electricity-based fuels and feedstocks, and hydrogen could be the gamechanger.

“A key differentiator is hydrogen’s massive potential in traded energy markets. Low-carbon hydrogen and its derivatives could account for around a third of the seaborne energy trade in a net zero 2050 world.”

Between now and 2050, Wood Mackenzie forecasts global demand for hydrogen to increase between two- and six-fold under its Energy Transition Outlook and Accelerated Energy Transition (AET) scenarios. Under its AET-1.5 scenario (1.5 °C warming), low-carbon hydrogen demand reaches as much as 530 million tonnes by 2050, with almost 150 million tonnes of that traded on the seaborne market.

Low-carbon hydrogen import demand from North East Asia and Europe could account for about 80 million tonnes, equivalent to 55% of seaborne hydrogen trade, and 23 million tonnes (16% of total seaborne energy trade), respectively.

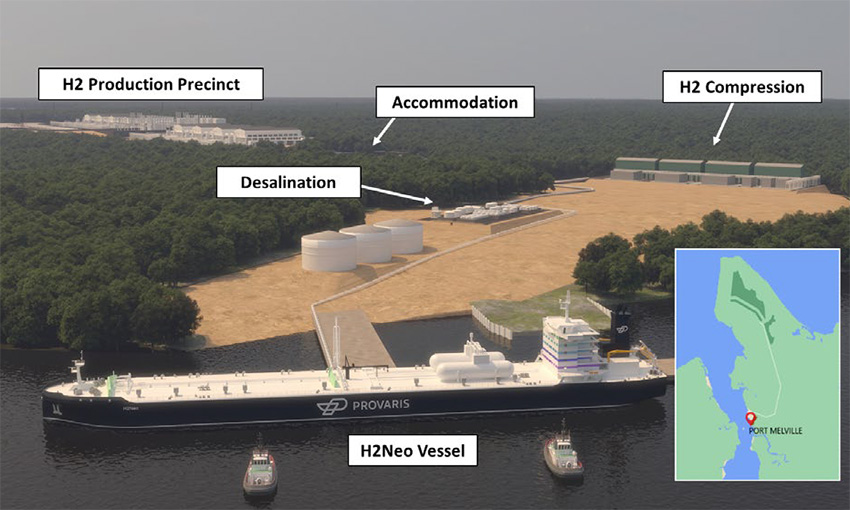

Several countries are hoping to benefit from developing export-oriented hydrogen megaprojects, with blue and green hydrogen projects being developed in Russia, Canada, Australia, and the Middle East.

In the burgeoning green hydrogen space, nearly 60% of proposed export projects are located in the Middle East and Australia, principally targeting markets in Europe and North East Asia, according to Wood Mackenzie.

Over the last 12 months, there has been a 50-fold increase in announced green hydrogen projects alone, the firm reported.

Wood Mackenzie vice chair Gavin Thompson said, “While no two hydrogen export projects look the same, the most obvious difference in proposed projects is between blue and green hydrogen. But portraying this as an either-or choice is an over-simplification”.

While current costs of green hydrogen production are typically more than three times higher than those of blue hydrogen, green hydrogen costs are expected to fall as electrolyser manufacturing technology improves and renewable electricity costs decline.

An expected drop in costs will support a longer-term pivot from blue to green hydrogen. However, each market has unique characteristics and cost declines will not be uniform.

“The reality is that the world needs both to achieve the required pace of global decarbonisation. Blue hydrogen production has a scalability advantage over green hydrogen at present and can already be developed in the requisite volumes, though lead times are longer,” Mr Thompson said.

“Most proposed projects are currently a combination of the two. A blue hydrogen exporter in Australia or the Middle East, for instance, could establish a market position while expanding into green hydrogen as costs decline over time and capacity becomes available.

“Producers could thus build out their low-carbon hydrogen supply chains as green hydrogen becomes more competitive over time.”

Based on Wood Mackenzie’s analysis of future costs, Australia and the Middle East sit in the top echelons for solar irradiance and offer massive green hydrogen potential. With conversion and transport costs making up as much as two-thirds of the delivered cost of the interregional hydrogen seaborne trade, proximity to market will also be important.

For supply to North East Asia, for instance, suppliers in Australia would appear to be ahead of the pack.

“The irony remains that the dynamics of the future global trade in hydrogen are likely to look similar to those of traditional fossil fuels,” Mr Thompson said.

“North East Asia, including China, and Europe will be the big importers of hydrogen; Australia, the Middle East and, possibly, Russia and the US have the greatest potential to be big exporters.”