CONGESTION continues to plague global container ports with little sign of abating. Delays continue to negatively impact global supply chains, causing frustration for shippers and other stakeholders in the global trading economy and slowing the pace of the general trade recovery.

The following excerpts from a recent report by IHS Markit provide insight into the problem and examine various solutions.

The direct operational cause of the congestion is excessive growth in average call sizes, or the average number of containers loaded, restowed and unloaded per container port call.

Prior to the pandemic, call sizes were already growing strongly due to increasing vessel sizes and optimisation of liner networks. Strongly rebounding and unpredictable demand as trade volumes recovered sharply in 2020 H2 and continue to grow through 2021 has amplified the trend causing delays at many global ports that under normal circumstances can handle intermittent spikes in demand and taking others beyond their operational breaking points.

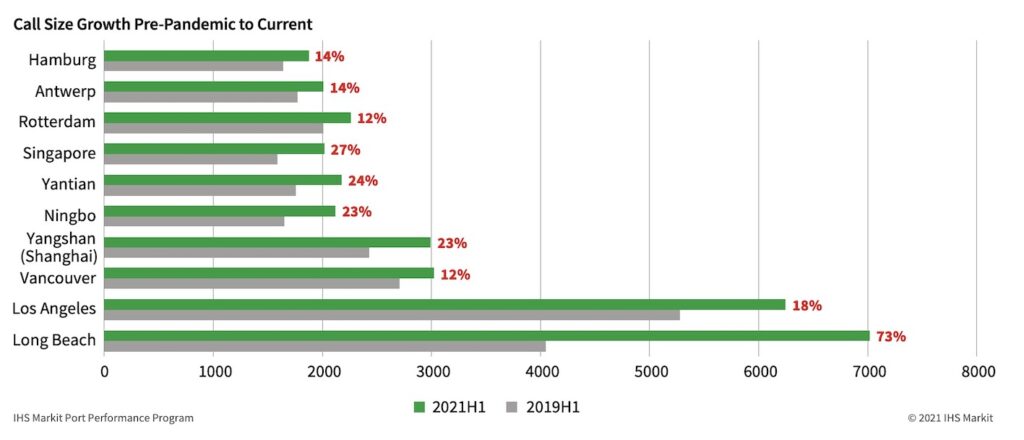

At the Port of Long Beach in the United States, average call sizes are now more than 70% higher than before the pandemic. Long Beach terminals are dealing with an average of more than 7000 moves per call on large ocean-going vessels. Other major US, North European and Asian gateways are dealing with call sizes that are between 10% and 30% larger than two years ago.

For these ports, the severity of the operational strain due to the surge in volumes is in large part because the cargo is coming into terminals in much more concentrated loads. This is placing heavy stress on ocean and landside operations, increasing yard congestion and cargo dwell times, with knock-on effects on equipment repositioning and intermodal links further fuelling the problem and resulting in sustained congestion at key global gateways.

The phenomenon has been a shock to many both inside and outside the industry and has prompted investigations into why certain container ports have become overwhelmed, and what can be done to improve resilience for the future.

Quality terminal assets and sufficient physical capacity to handle sudden surges in demand is an obvious requirement but spending on infrastructure alone is not going to be the solution. Port infrastructure is expensive, takes time to build, and most port operators do not want to have assets and capacity lying idle purely to deal with the possibility of unexpected demand surges.

Improving operational processes is often a more realistic option. All major ports have room for efficiency gains through smarter leveraging of digitisation and data sharing to streamline processes and improve co-ordination between the many actors involved in complex operational processes such as port calls.

The potential for time and cost savings through increasingly digitised and data-driven processes are well recognised globally and there are numerous types of projects and programs underway. The current congestion phenomenon will very likely accelerate this trend which will be bolstered further by the industry decarbonisation agenda with initiatives like port call optimisation already identified by the IMO as an important strategy to reduce global emissions from container shipping.

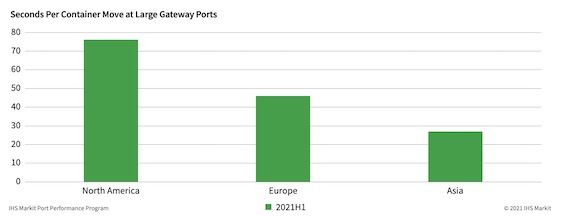

A third option is to simply add brute force to move containers more quickly. The potential of this as a solution is very clear when we examine the large gap in performance between container ports in different global regions.

The Chinese ports of Yantian, Ningbo, Yangshan (Shanghai), and Singapore in South East Asia, require an average of 27 seconds to move a container on large call sizes (taking into account all vessel waiting and cargo operations time). This compares with 76 seconds required at the major North American gateways of Los Angeles, Long Beach and Vancouver, and 46 seconds at the North European ports of Antwerp, Rotterdam, and Hamburg.

Vessel waiting times tell a similar story. Our port performance data show a much higher percentage of calling vessels required to drop anchor at the North American ports in 2021 H1 compared with Asia and Europe, and when they do, the average number of hours they need to spend at anchor before getting a berth is five times more than in Asia and three times more than Europe.

Part of the gap in efficiency is probably due to differences in supply chain and port call profiles between the three regions. Large North American west coast gateways are generally dealing with larger call sizes (more concentrated cargo operations) as well as potentially higher levels of intermodal complexity with a higher proportion of imports for consumers than the more export-focused set-up of Asian ports.

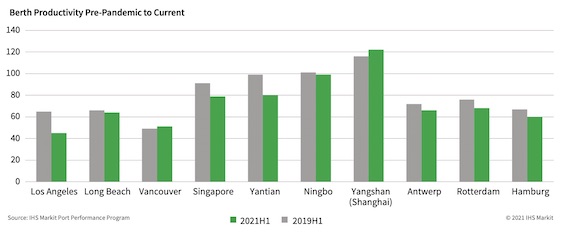

Berth productivity – container-moves-per-hour while vessels are at berth – is an important factor. Berth productivity at the Asian ports is consistently around one third higher than North America and around 25% higher than Europe. This difference is in large part due to round-the-clock operations that add vital operating hours so work can be completed more quickly at Asian ports. Cost and availability of labour is also important.

There are few indications that the congestion will significantly improve over the short term and failing a sudden sharp drop in demand we expect bottlenecks at ports and congestion-related effects to continue until at least the end of the year.

Over the longer term, there may be after effects on the structure of supply chains. Shippers and their logistics partners are increasingly concerned with port performance and undertaking more programs around risk profiling of gateways and investigating alternative transportation and sourcing options. This will likely result in more appetite and improved capability to diversify sourcing and further develop risk management strategies like dual sourcing or so-called “China + 1”, particularly for product categories with simpler supply chains.

The congestion phenomenon continues to highlight lack of resilience in the global container shipping system particularly in relation to gateway ports and their primary function to support global trade.

As port and terminal operators come under increasing pressure to investigate and improve, we expect to see more programs around initiatives like automation, extended operating hours and process improvement achieved through digitization and more data-driven analysis.